Within moments of the inaugural address, Ald. Bernard Stone was telling the press portentously: 'That was a unifying speech. I think we're all united now. Maybe not the way he wanted, though.'"

- Jeff Lyon for the Chicago Tribune Magazine, 'Council Wars: The Battle for City Hall,' October 31, 1993

Thus far we've covered the early history of the tenant rights movement. We learned about the events that led to the drafting of the Uniform Residential Landlord Tenant Agreement (URLTA), a document that was offered as a blueprint for landlord-tenant laws nationwide. We saw how the powerful real estate lobby prevented the Illinois general assembly from enacting URLTA and almost all other laws that might have protected renters, leading to Evanston's creation of their own city-specific Landlord Tenant Ordinance in 1975. At long last we're able to look at the creation of the infamous, unique and peculiar Chicago Residential Landlord Tenant Ordinance (CRLTO).

1975-1978: Agonizing

In early 1975, Chicago renters had only the most basic of protections against bad landlords. The only laws on the books to addressing landlord-tenant relations were the scant few that had squeaked out of Springfield and the courts. Chicago had a fair housing ordinance. Landlords were liable for the condition of apartments when tenants moved in, and for keeping those apartments in habitable condition while the tenants lived there. Landlords couldn't evict a renter if they complained to the government about code violations in their apartments. Landlords couldn't get in the way of a tenant who wanted to sublease their apartment, but they could still charge the tenant an arm and a leg for the ability to do so.

That was it.

There was no way for tenants to recoup the cost of making repairs on their own if a landlord didn't do so. Landlords could still testify on behalf of their tenants in eviction court without providing them notice beforehand. Landlords could enter apartments with no advance notice. They could hide the name and address of the real building owner behind aliases on the lease. They could collect security deposits with no guarantee of returning them and no need to pay interest to the tenants for the time they held onto the money.

Chicago had recently been accused of having some of the worst housing in the nation. The segregationist zoning policies of the 1940s had deliberately lumped the poorest residents of the city together in slums and housing projects. The worst apartments lacked heat, running water, working toilets, smoke alarms, locking doors and functional windows. Landlords entered apartments without notice, evicted tenants without notice, stalled on making repairs, and took advantage of vacationing renters by claiming their apartments to be "abandoned" and selling off their belongings.

Grace and Byron Watkins

Social worker (Byron) and musicologist (Grace). Rogers Park residents, tenant organizers, code violation whistleblowers. Won a lengthy legal battle against landlord's attempt at retaliatory eviction which was extensively covered by the Chicago Tribune.

Image via the Chicago Tribune

Ed Sacks

Chicago tenant activist and “professional apartment liver.” In 1978, published Chicago Tenants' Handbook. Wrote “Apartment Watch” column in Chicago Sun-Times from 1992-2009.

In the far north neighborhood of Rogers Park, members of the Rogers Park Community Council created a splinter group to address the issues affecting renters. One of the founders of the Rogers Park Tenants Committee was a history professor by the name of David Orr. The group would eventually become a major player in the push to enact the CRLTO.

The Chicago Real Estate Board came out with a new version of their fill-in-the-blank lease. The old one, called “Form 12-R,” had been roundly criticized for including a “confession of judgment” clause that required tenants to waive their right to represent themselves in eviction court. Such clauses were still legal in Illinois, but many other states had outlawed them and consumer protection advocates stated that they were terrible. The new form, “Form 15”, removed the confession of judgment clause but was still written in such heavy legalese that neither landlords nor tenants could easily understand it.

The lease was basically the end-all and be-all of apartment life. Any disputes that made it to court fell back on the text of the signed lease. The only people who could understand the lease were large landlords with easy access to attorneys, so they had all of the power in rental housing.

In 1976, Mayor Richard J. Daley did put together a committee to discuss implementing rent control in Chicago, but nothing came of it. In 1977, a security deposit law finally came out of Springfield, although landlords relied on tenants not knowing about it and continued to retain deposits and skip out on paying interest.

By 1978, tenant rights groups were all over the city. What had started with tenants organizing within individual buildings in response to Dr. King's civil rights actions in the late 1960s had blossomed into neighborhood tenant advisory groups. Combined with low cost legal clinics popping up across the city, renters were starting to get educated about their rights.

In February of 1978, the Chicago Council of Lawyers created an alternative fill-in-the-blank lease form that was easier to read and less heavily biased in favor of landlords. They made it available in corner stores just like CREB's “Form 15.” Included in the lease was a clause allowing renters to make necessary repairs and deduct the cost from their rent payments – the same right that had caused Realtors to shut down URLTA in the state legislature. Large-scale landlords did not adopt the new alternative lease, worried that tenants would deduct repair costs for major damages that they'd deliberately caused themselves. Some smaller landlords did make the switch, simply because it was easier to read.

In May, Rogers Park residents Grace and Byron Watkins became the darlings of the newspapers when their landlord evicted them for organizing the tenants in their building and complaining to the city about the conditions. With the help of a pro bono attorney, the Watkinses would continue to fight the eviction for the next four years, appearing in court over 30 times. Tribune updates on their case were always accompanied by expert opinions about the rights of tenants, helping to spread knowledge to the entire renting population of Chicago.

In the fall of 1978, tenant advocate and renter Ed Sacks published the first edition of the “Chicago Tenants Handbook,” with advice on everything from apartment hunting to which clauses tenants should cross out in Form 15.

Fly-by-night apartment brokers were abundant in Chicago. They were notorious for using bait-and-switch techniques and for using illegal segregationist tactics. The state of Illinois threw a bone to city renters in September when they started requiring agents working in the rental industry to have licenses just like agents who sold houses. They followed up on the new law by cracking down on most of the unlicensed agencies in the city.

1979-1982: Organizing

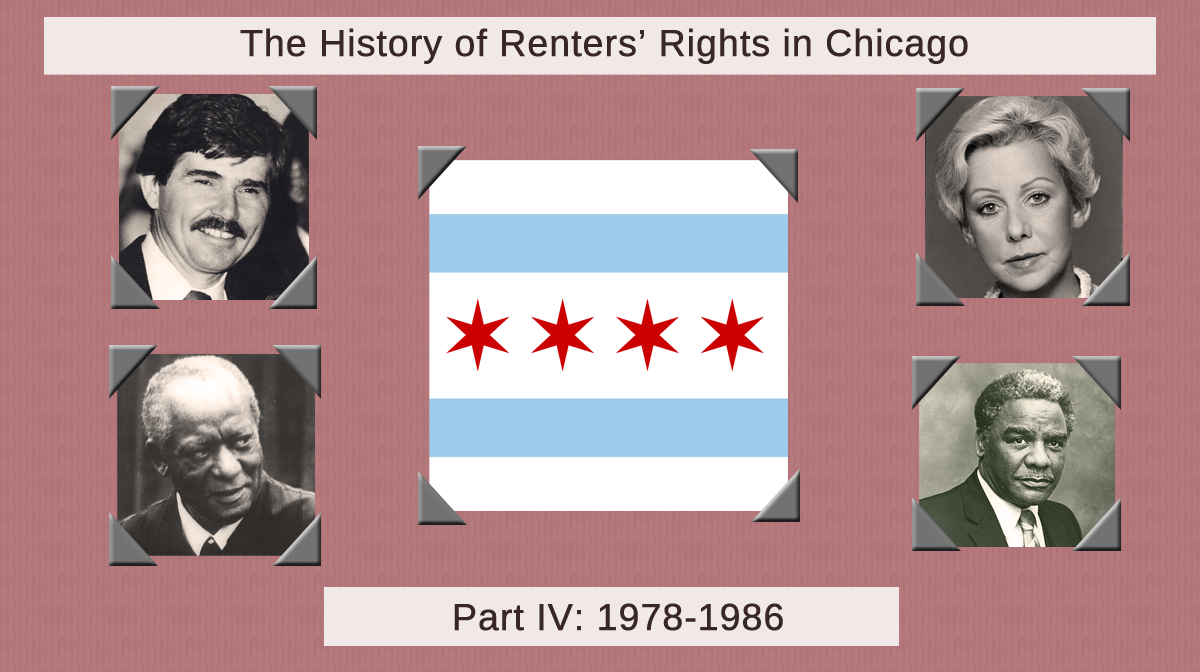

Jane Byrne 1933-2014

Chicago mayor from 1979-83, first female mayor of Chicago. Moved into CHA public housing at Cabrini Green to draw attention to the living conditions and violence there, but failed to support the pending Tenants' Bill of Rights in the city council.

Chicago has not had a Republican mayor since 1931. The Democrats consolidated their power through a system known as machine politics. They gave government jobs to well-connected members of minority groups. In the 1930s those groups were still European immigrants: Irish, Polish, Czech and Jewish. In return those leaders would drum up enormous voter turnout in favor of the candidates selected by the Cook County Democratic Party. The Machine dominated Chicago's political landscape for over 50 years. By the late 1970s, mayoral races were not Republican/Democrat, as the Republican party had been rendered ineffective by the power of the Machine.

In machine politics money didn't only talk. It shouted. Bribes flowed freely throughout the city government. The city owns a lot of land. Real estate investors who wanted the best deals on that land gave money to political candidates with the expectation of receiving favors in return. The first Mayor Daley bult up Chicago's Loop by assembling a powerful support base of real estate developers, brokers and investors - in other words, landlords. They had the money and they ran the city.

On Daley's support team was a woman by the name of Jane Byrne. In the spring of 1979, Byrne became the first female mayor of Chicago. She was not the chosen machine candidate, but her election tactics were taken straight from the machine handbook. However, instead of focusing her recruitment efforts on the traditional Democrat power base, she turned to the black community. She promised reform to the residents of the housing projects, and in turn they voted her into office.

However, Byrne had to fight an enormous battle against the machine to get elected. In the end her campaign cost her over $10 million, and that money didn't come from the residents of the projects. It came from big business donors – the same real estate developers and brokers who had curried favor with the machine for decades. No matter what she promised to her black supporters, any hope of a tenant bill of rights passing under her watch was doomed from the start.

David Orr B. 1944

Anti-machine Democrat and co-founder of Rogers Park Tenants Committee. As 49th ward alderman, sponsored the bill that would become the CRLTO in the Chicago City Council. Has served as the Cook County Clerk since 1990.

The election of 1979 also saw another person head down to city hall: David Orr of the Rogers Park Tenants Committee, now alderman of the 49th ward. Orr ran as an independent, non-machine Democrat. He would remain committed to that stance for years. Just two months after his election, Orr was getting ready to present a rent control ordinance to the city council. It would die in committee, along with every other tenants rights proposal he submitted, for the rest of Byrne's tenure as mayor.

Come the fall, when peak moving season came around to Chicago, tenants faced an extremely low apartment vacancy rate of 2.81%. Rent rates had increased nearly 20% in one year. (In 2016 we've been seeing a vacancy rate of between 4-5% and increases of about 3-4% per year.) The Chicago city council was considering the creation of a fair rent commission and restrictions on condo conversion, but both proposals had been killed in committee due to the powerful real estate lobby.

Real estate industry leaders wanted to create an advisory commission consisting of legislators, Realtors, architects and developers to handle keeping rent rates in line – note the absence of tenants from that list. They advocated for the creation of more rental housing rather than implementing rent control. They also wanted to eliminate the existing building health and safety codes claiming they were outdated. While the building codes may have been outdated, they were also still the only thing tenants could use to defend themselves in eviction court.

Ed Sacks had submitted a proposed Tenants' Bill of Rights to the Illinois General Assembly, which was at the time considering a separate landlord-tenant act that was seen as anti-tenant. It died in committee like all of its predecessors.

As we entered a new decade, URLTA had been adopted in 15 states and was being considered in 8 more. Illinois was, of course, not one of them. The American Dream of homeownership prevalent in the 1950s and 60s as a result of the New Deal was slowly falling by the wayside. Middle class residents were starting to realize that their children might wind up renting for their entire lives.

The tenant rights movement was slowly becoming a cause of the middle class instead of a humanitarian fight for the poor and disenfranchised. A bill was even before the Illinois legislature that would have made it illegal for cities to ban the conversion of apartments into condos as Evanston had done two years earlier. More condos would have made it more possible for the middle class to buy housing, but would have also removed even more affordable apartments for the poorest residents of the city.

Metropolitan Tenants Organization

Coalition of neighborhood groups formed in 1981 as tenants' response to the real estate lobby. Battled rising rent, arbitrary evictions, and condominium conversions. Lobbied for passage of CRLTO.

For the time being, though, the addition of educated, middle class renters into the tenant rights battle gave more of a backbone to the numerous tenant rights groups that had emerged in neighborhoods across the city. In 1981, 250 representatives from tenant rights groups met at the Chicago-Kent College of Law to discuss creating a citywide tenants union. The National Tenants Union assisted them with the process of organizing into a larger group. In November they met again at the Depaul Loop Campus to officially unite as the Metropolitan Tenants Organization, an advocacy group that still exists today.

Also in 1981, Mayor Byrne had moved from her posh Gold Coast home into a squalid apartment in Cabrini-Green as a publicity stunt to protest the high crime rates in the projects. When she barely spent any time there, the residents saw through her, and were outraged that they were being used to advance her political agenda. Her stay didn't do anything to advance tenants rights at the time, but it did galvanize her former support base against her. They became convinced that the only way they would see improvement would be to put one of their own into the Mayor's office. Deprived of the voter base that had put her into office, Byrne's days as mayor were numbered.

Thanks to the efforts of the MTO, tenants rights became a major talking point in the mayoral election campaigns of 1982-83. By this time, Alderman David Orr had written and submitted a draft of what was then called the “Tenants' Bill of Rights,” based on URLTA and Evanston's RLTO. It had died in the Building and Zoning subcommittee of the city council.

The candidates for mayor in 1982 were incumbent and machine candidate Jane Byrne, black independent Democrat Harold Washington, and Republican Bernard Epton. Tenant rights activists attended nearly every event in the campaign, keeping the Tenants' Bill of Rights at the forefront of discussion. The nature of the candidates meant that this would be a civil rights battle as well as a political event.

Byrne promised to create her own alternative bill of rights and would not commit to passing Orr's version. Washington's platform included strong support for a fair rent commission and for passage of the bill.

It became obvious that Byrne's support had eroded substantially. However, white voters were terrified that the election of a black mayor would tank the city's bond rating. For the first time, many independent voters chose to vote for Epton instead. Epton played on their fears, portraying Washington as a pervert, a criminal, and a patsy for south side gang leaders. His position on tenant rights was that Chicago should continue waiting for Springfield to handle the matter rather than making it Chicago's problem.

1983-1986: Legislating

Harold Washington 1922-1987

Chicago mayor from 1983-87. First black mayor of Chicago, running against the Democratic machine. Supported passage of Tenants' Bill of Rights, but was blocked by Chicago City Council. After a new council approved it, he signed the CRLTO into law in 1986.

Harold Washington was elected mayor in 1983. He had run a grassroots campaign funded by small donations from individual citizens, so he wasn't beholden to big business or the real estate lobby. As a result, his first term was the best shot that renters would have to push through a tenants' rights bill.

The city had overcome their fear of a black mayor because Washington was against the corruption and bribery that had plagued city hall for decades. However, this political stance became an issue as divisive as his race when he came up against a city council still dominated by white machine Democrats. For the next three years, a near super-majority of 29 white aldermen led by Eddie Vrdolyak were able to kill every proposal Washington tried to push through. City legislation came to a grinding halt.

By 1984, Orr had the backing of 7 other aldermen for his Tenants' Bill of Rights, now called the proposed Chicago Residential Landlord Tenant Ordinance. It included the following provisions:

- Renters could make repairs and deduct the cost from their rent

- Renters couldn't be forced to waive rights granted by city, state or federal law

- Renters couldn't be evicted in retaliation for complaining to the government or the media

- 2 days notice would have been required from the landlord before entering an occupied apartments

- Renters could pay reduced rent if their apartment was damaged by catastrophe

- Landlords couldn't consider an apartment abandoned and confiscate all of a tenants' belongings until they had been gone for at least 21 days, hadn't paid rent, and hadn't informed them that they planned to return.

- Security deposits would have been capped at 1.5 months rent.

All but the last provision would eventually make it into the CRLTO. However, as a proposal endorsed by Washington, Orr's ordinance remained stuck in committee. 40 neighborhood tenant rights groups across the city submitted a petition for passing the bill with 10,000 signatures, but to no avail.

In 1985 with the "Council Wars" still ongoing, Realtor groups started picking the ordinance apart. They stirred up owner-occupants of small apartment buildings, staging protests of their own. In response, Orr add a section outlining tenants' responsibilities to make the proposal more balanced. He was forced to exempt small owner-occupied apartment buildings completely. The proposal continued to languish in committee. MTO provided the Tribune with evidence that 10 aldermen, including 8 on the Building subcommittee, had accepted huge donations from real estate companies opposed to the CRLTO.

If things had proceeded as normal in city hall, the “Council Wars” would have continued through the end of Washington's first term in 1987. However, Washington was aware that the city voting districts did not reflect the actual racial makeup of the city. The council was 66% white, 32% black and 1% hispanic, while the city population was 40%/40%/15%. He sued the city to force them to redraw voting district boundaries and won. In 1986, seven wards had their boundaries redrawn, forcing a special election to replace those seven aldermen. The change in council members was enough to break the stalemate. The white machine aldermen lost the ability to kill Washington's proposals without bipartisan support.

The new majority leader of the city council was none other than David Orr.

Washington's supporters knew they only had a year left in his term and didn't waste a minute. In May of 1986, before new committee assignments were even completed, Alderman Larry Bloom was ready revive every Washington proposal that had been rejected by the previous council. Included in that group was the CRLTO.

On August 18, the Chicago Board of Realtors tried a tactic that had worked a decade earlier to kill URLTA at the state house: they submitted an alternative ordinance. Their version gutted the repair and deduct clause along with several other hot-button topics. They said they were doing it to “save their business and to save Chicago.” They painted a frightening picture of a future Chicago after the passage of Orr's CRLTO: a desolate, abandoned shell of a city where developers and rehabbers had stopped buying property because the laws were too hostile towards landlords.

This time the ploy didn't work. Ten days later on August 28, 1986, the CRLTO finally made it out of committee. Aldermen Bernard Stone and Fred Roti of the Buildings and Zoning subcommittee broke with the machine party line and voted in favor of it. At the time, Roti estimated a cost to the city of $300,000 to 500,000 to enforce the new ordinance due to the increased need for building inspections.

On September 8, 1986, the CRLTO passed the city council by a vote of 42 to 4 against. Of the four who voted against it, only Ed Burke remains in the council today. Alderman Vrdolyak, leader of the machine bloc, was conspicuously absent on the day of the vote. Half of the rules were to go into effect the following month, the rest at the start of the new year. Chicago tenants finally had their bill of rights, much to the chagrin of the Chicago Board of Realtors, who immediately sued the city.

Hon. James Parsons (1911-1993)

First black federal district judge in continental United States. Upheld constitutionality of the CRLTO, but described it as “harsh and revolutionary.”

The case of “Chicago Board of Realtors v. City of Chicago and the Metropolitan Tenants Organization” was filed on October 14, 1986, requesting an temporary restraining order against the ordinance taking effect, which was granted. The case was fast-tracked through the judicial system, reaching a judge just days later. A preliminary verdict was handed down on November 3 in favor of the city of Chicago. The judge in charge of the case was James Parsons, who had broken ground as the first black federal district judge when he was appointed by President Kennedy in 1961.

The Realtors' case argued that the exemption of small, owner-occupied buildings that they had fought so hard for two years prior was unconstitutional because it denied equal protection from the new law for all owner-occupied buildings.

They also argued that the scope of the ordinance gave more police power to the city than permitted by Home Rule.

Finally, they argued that the following requirements all violated the 14th amendment of the US Constitution, depriving landlords of their rights as property owners without due process of law:

- Requiring 2 days notice before they could enter an apartment

- Having to open a second bank account for security deposits

- Having to give receipts for security deposits

- Requiring landlords to pay interest on deposits at a rate set by the government

- Making subsequent owners of a building liable for the deposits collected by a prior owner

- Requiring disclosure of the owner's actual name and address

- Requiring disclosure of code violations and utility shut-off notices from the past 12 months

- The ability of renters to make repairs and deduct the cost from their rent

- Allowing tenants to obtain substitute housing in case of emergency at the landlord's expense

- Preventing eviction if a landlord accepts a rent payment after filing an eviction case

- Limiting late fees to $10

- Making one-sided leases illegal

- Forcing landlords to include a summary of the ordinance with every lease

- Extending the definition of “retaliatory eviction” to include landlords who failed to issue lease renewals as a response to tenants who complained about housing conditions to the government or the media

Given that every one of those disputed clauses still exists in some form or another in the CRLTO today, it's pretty obvious how the case turned out. Judge Parsons found that the law did not infringe upon the constitutional rights of landlords. He ruled in favor of the city, although he expressed his doubts about the ordinance in his verdict, calling it “highly questionable if not substantially inadvisable.” The Realtors appealed, but in May of 1987 the appeal was denied. There would be no further challenges.

Mayor Harold Washington was re-elected in 1987, this time with the backing of all those big donors who had shunned him in 1982. Washington died suddenly in November of 1987. As President of the City Council, David Orr became acting mayor for 8 days until Eugene Sawyer was appointed to complete Washington's term. Orr remains involved in local politics to this day, currently serving as Cook County Clerk.

As for the CRLTO, it has remained largely unchanged since its passage. The tenant movement has largely died out. Landlords who had gritted their teeth through the tenant activist era of the early 80s waited for renters to lose momentum and then immediately went back to business as usual. On Monday we will look at what's happened to tenant rights in Chicago in the thirty years after CRLTO, and how a law meant to help the poor has been largely derailed by everyone else.

RentConfident is a Chicago startup that provides renters with the in-depth information they need to choose safe apartments. Help us reach more renters! Like, Share and Retweet us!

Check out all of the articles in the "History of Renters' Rights in Chicago" series!

Part 1: “This Was No Church” (1881-1963)

Part 2: The Three-Front War for URLTA (1964-1972)

Part 3: The Sovereign State of Chicago (1972-1981)

Part 4: Highly Questionable if not Substantially Inadvisable (1978-1986)

Part 5: From Rights to Revenge (1986-2016)

Want to find out more? Check out the list of all 140+ research sources used to create this series.